Megapapers and How to Write Them

Papers that combine the insights of many people, disciplines, and organizations have a lot of benefits, but there aren't enough of them.

Introduction

I am a big fan of reading megapapers and want to see more of them in the world.

In this article – which I wrote as a means of procrastinating on an actual megapaper – I will:

Explain what a megapaper is and how it’s different from other seemingly similar kinds of papers;

Argue that megapapers are valuable but also predictably rare;

Describe some lessons I’ve learned over the years about how to lead or contribute to megapapers.

Definition and personal context

I’ve done various things in my career, and one common thread is helping make megapapers happen.

By megapaper, I mean a research paper/report that involves a large number of authors (roughly 20+), institutions (roughly 15+), and disciplines (roughly 10+), with these authors and institutions being drawn from multiple sectors (2+ out of academia, civil society, industry, and government).

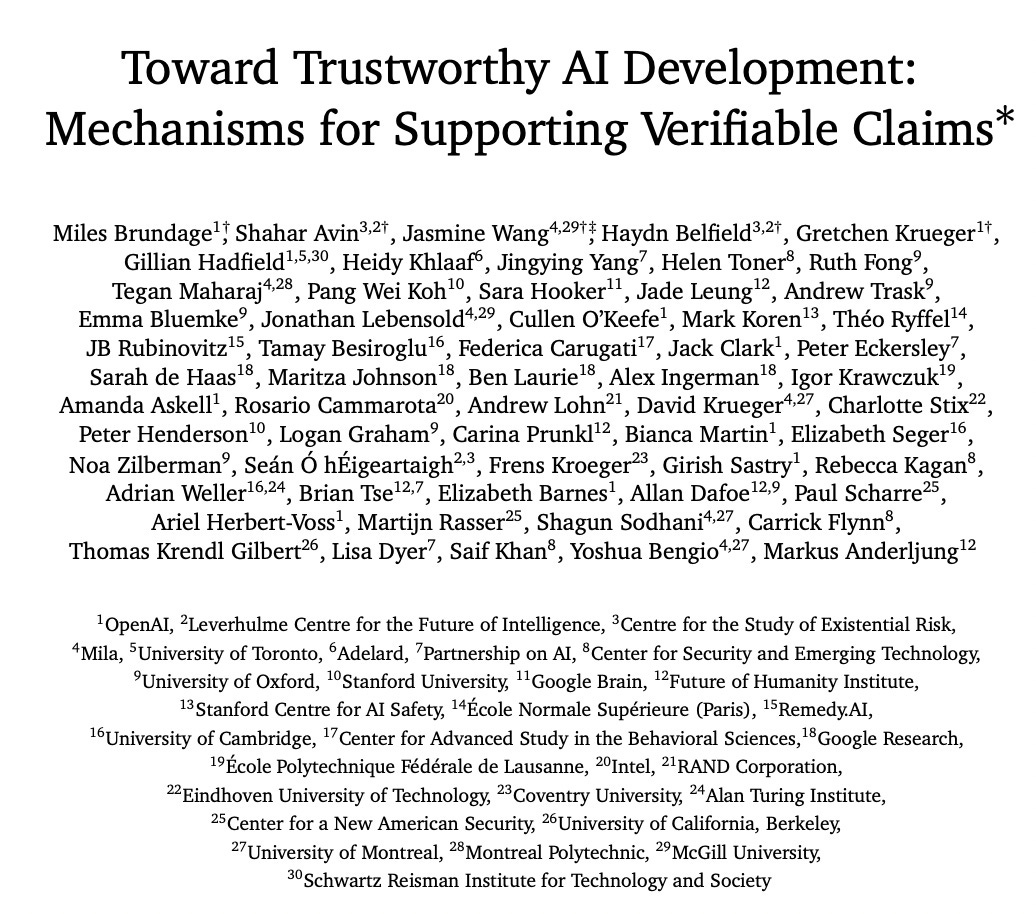

The author list for the mega-est megapaper I have coauthored so far. As discussed below, the number and diversity of authors is, critically, not just for show but a reflection of the range of expertise brought to bear on the paper’s overall thesis and various specific claims.

The prefix “mega” is intended to convey the unusual breadth and depth involved compared to a typical paper as well as the wide range of contributors/contributions. I use this term in order to nod toward “megaprojects” (which are a fascinating field of study in their own right – read How Big Things Get Done by Flyvbjerg and Gardner for an excellent introduction).

Some examples of megapapers that I have contributed to include:

One that I advised on at a high level but didn’t coauthor is Personhood Credentials.

Some AI policy-related megapapers that I was not involved in include Open Problems in Technical AI Governance, Foundational Challenges in Assuring Alignment and Safety of Large Language Models, and the International AI Safety Report.

Comments on the definition

There is a spectrum of mega-ness. The most mega of megapapers is perhaps an IPCC report, since these draw on thousands of scientists and institutions, have a high bar for rigor and precision, and involve at least dozens of disciplines. But I will mostly focus on more moderate cases here.

The part of the definition about disciplines is important and rules out “normal big papers” in a specific discipline.

Megapapers are a specific type of “intellectual megaproject,” of which other examples include encyclopedias and the creation of new research fields.

Wikipedia is a much larger intellectual megaproject than any megapaper, but does not advance a specific argument or worldview in the way that a megapaper does.

There is sometimes a fine line between a megapaper and an edited volume depending on how cohesive the volume is, but generally I exclude those since they are almost never integrated into a cohesive whole, which is a key aspect of megapapers as I conceive of them.

There is something distinctive about megapapers which makes them different from the above, and in need of more investment.

Why megapapers are important and rare

Megapapers are important because:

They combine bits of knowledge that are normally siloed in different industries and disciplines, and interesting things sometimes happen when this combination occurs;

The amount of “intellectual heft” that is brought to bear on them serves as a costly signal of the importance of a new area of inquiry, and can help “crowd in” new intellectual investment;

Some topics are sufficiently complex that they can’t be tackled without a “mega” approach;

They can provide a trustworthy “one-stop shop” so newcomers to an area of inquiry can get up to speed on almost everything that is known in that area, and then push beyond it.

They’re rare, though, because:

They require exercising a lot of skills that are not normally valued highly in academia (e.g., large project management, interdisciplinarity);

Credit for them is inherently diffused across the many authors;

They involve pulling together a new intellectual topic/framing/field that, before the publication and dissemination of that paper, is not recognized as “a thing,” or that thing is viewed as too unwieldy to be summarized in its totality;

By nature, they raise tricky issues around framing, structure, scope, etc.

An aside on system cards

“System cards” / “technical reports” about a particular AI model/system summarize a large amount of knowledge about that model/system. I would count these as megapaper-adjacent in that they meet most of the properties but not all (i.e., they involve many authors and disciplines but typically a single institution and sector).

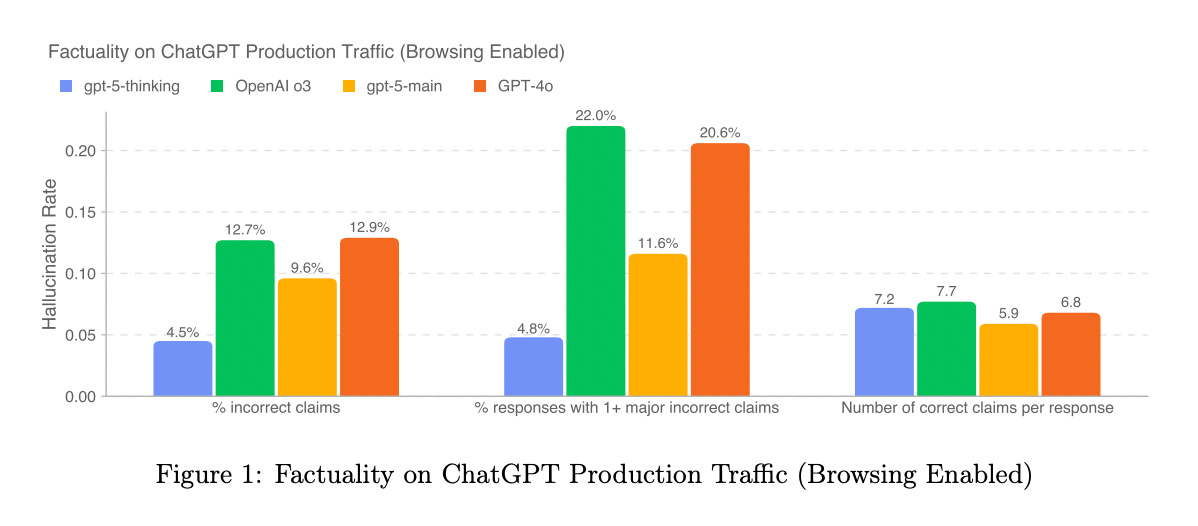

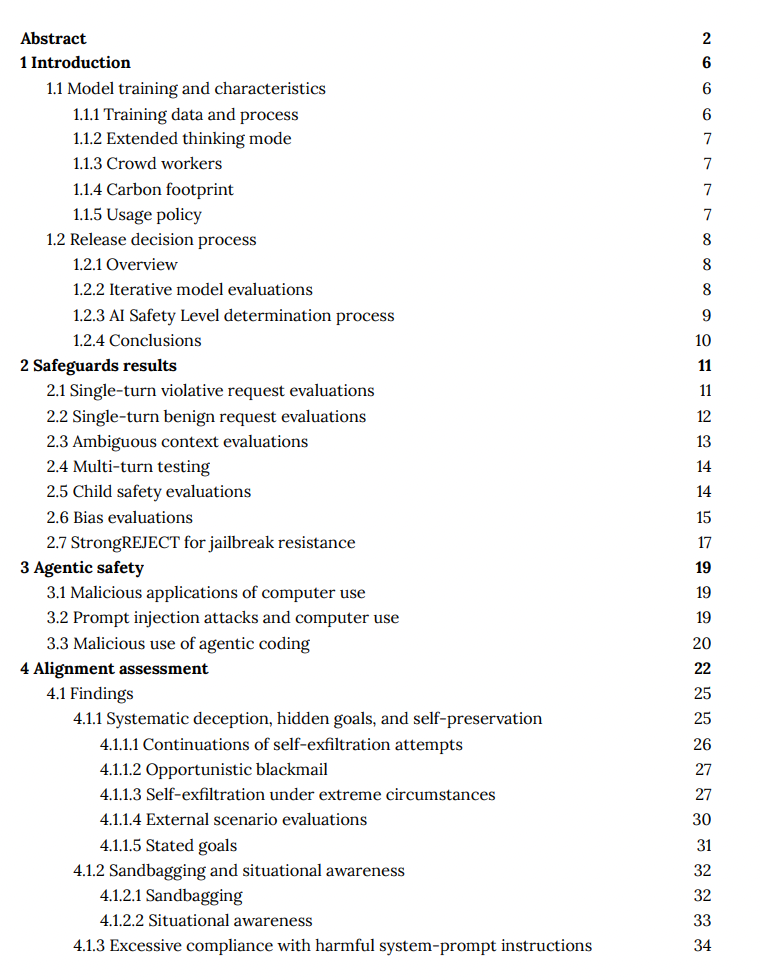

An excerpt from the GPT-5 system card, and the beginning of the table of contents for the Claude 4 system card.

There is another notable distinction, as well. For a typical system card/technical report, the writing process is not when the majority of the intellectual work happens – rather, a bunch of work happens naturally as part of the process of making the model/system in the first place, assessing its properties, designing/testing mitigations, and preparing it for launch, and then the authors “skim the cream off the top” of all of that existing work and package it as a paper.

OK, so how do you write a megapaper?

Overall project sequence

The rough order of operations is as follows, although there are many possible variations on this theme:

Establish an initial core of authors and a high level vision. This could involve hosting a kickoff workshop, which may or may not have “writing a megapaper” as an explicit goal stated beforehand.

Recruit more authors who bring additional expertise to bear and complement the core authors (sometimes joining the core), in parallel with initial drafting.

Hold regular meetings among the core group to decide on questions related to framing, adding new authors, editing, aligning on a communications/launch plan, getting approval from people’s home organizations for any policy claims / recommendations made in the paper, etc.

Do final editing (including bringing in graphic designers, copy editors, etc. as needed), getting feedback from a very wide set of people (necessary given how many disciplines are implicated!).

Run the actual launch smoothly and ambitiously, possibly with a dedicated website and certainly with at least one blog post, and probably multiple coordinated blog posts.

Do ongoing maintenance/nurturing of the community that sprang up or springs up around the paper.

Things aren’t quite this linear in practice – you should think about the comms plan to some extent early on since the whole point is to have some sort of impact on how people think about things. You should be ready to make framing changes based on late-stage discussions if truly necessary. And so forth. But hopefully this gives a rough sense of the themes at different time periods.

The remaining sub-sections give more specific guidance on how to address various challenges involved in megapapers.

Defining success

Different authors will have different reasons to participate, and that’s OK, but there needs to be some degree of coherence in order for key decisions to be resolvable.

Some goals I’ve had for papers include legitimizing an area of study or a category of policy interventions, raising awareness of a risk, distilling the received wisdom of a community into something that can be scalably communicated, and sparking interest among people from different disciplines on a specific topic.

Strange as it may seem, the narrative of the Malicious Use of AI report was perceived as pretty spicy and novel at the time, and I think it was effective in one of its goals: sparking more interest in and work on the topic. And yes, AI stock images like this were already a thing in 2018.

Motivations for different people getting involved

Some people will want to get a publication out of their time, which will help their career later; some will want to steer the finished product in a direction that they are more likely to agree with vs. what would happen by default; some want to lend their credibility to an area they think is important and deserves more attention; some want an excuse to start collaborating with someone; etc.

Depending on the motivation of a given prospective author and their skillset, you may want to approach them at different stages in the project and with different pitches. Some can be more trusted to own things end-to-end, some can generate lots of ideas but not filter them down, some are great at providing detailed feedback or wordsmithing, some will want to see that there’s “momentum” before joining in whereas others will want to have a foundational impact early on, etc.

Decision-making and division of labor

There needs to be a fair amount of top-down control in order to get things done and avoid the scope spiraling out of control, but going overboard risks creating something that is superficially mega in terms of authors listed, but actually represents just a few authors’ work (that is not a real megapaper in my book).

Overall paper-level strategic decision-making should generally be done by the core group with input from particularly affected authors, and a project manager should drive things forward day to day and make a bunch of smaller decisions autonomously.

Early on, the core authors should basically articulate the (early) overall structure and thesis together, and this process may take a while. Before too long, there should be section-by-section ownership and aspect-by-aspect ownership which is made explicit. There should be a bias towards overcommunication and a willingness to radically change divisions of labor based on different people’s bandwidth, how things are going in certain sections, etc.

It is absolutely critical to avoid collapsing into an “edited volume” vibe, though, and there has to be a high degree of coherence throughout, so there should be 1-2 people in the core author group that regularly do a full editing pass through the paper to make it work as a whole. Similarly, 1-2 people should take responsibility for getting the paper across the finish line, which can be exhausting as there are lots of setbacks along the way.

Barry Bozeman and Jan Youtie talk about different scientific collaboration styles in their work (e.g., here) and I think their “consultative collaboration management” style is basically the right one for a megapaper.

The cover of Bozeman and Youtie’s book referenced in the bullet above.

Credit assignment

Authorship order should be as fair as possible, and deviations from this (or ambiguities in how to achieve this) should be made explicit and transparent to the group. I might have some minor quibbles but basically Chris Olah has things right when it comes to handling authorship discussions here.

Don’t let anyone be an author if they didn’t contribute materially, at the very least through substantive feedback on the paper itself. This is demoralizing for people who put in serious work.

Listing authors’ main institutional affiliations is important for transparency but also can get tricky, especially for industry and government authors. Hedging language on the first page could be considered in order to allow some distance between the spicier claims in the megapaper and the institutions and authors involved. For example, see the footnote on the first page here, which has since been reused in various other megapapers since it enables people to participate in the intellectual work of a megapaper while also giving the host organization some plausible deniability if the paper sparks controversy).

The language that avoided a thousand conversations with Legal at different organizations. 😇

Rigor and peer review

It’s hard to compare the bar for rigor for a megapaper to the bar for a normal paper, since a megapaper’s scope tends to be larger, and there will not be any one person who can comprehensively evaluate every claim in it.

It can be tempting to lower the bar and get overly nihilistic about the prospects for effective peer review. If you do this, though, you are going down the road to slop, and not the road to a megapaper.

While literal formal peer review is probably a waste of time for megapapers, you should have serious informal peer review, with different reviewers asked to review specific sections or aspects of the paper comprehensively.

Tips for junior contributors

If you have less experience than the other authors, but want to use this paper to advance your career, you should start by proving yourself on a task that you do really well, and gradually ask for more responsibility. Find things that are being neglected (e.g., copy editing of certain sections, adding references), do them well, while making it very visible that you’re doing them and easy for your work to be supervised effectively (e.g., by sharing regular Slack updates and using Suggest Mode/Track Changes rather than directly editing the text). Make explicit at each step along the way what your expectations are in terms of authorship if you do well at your assigned tasks.

Implications of AI for megapapers

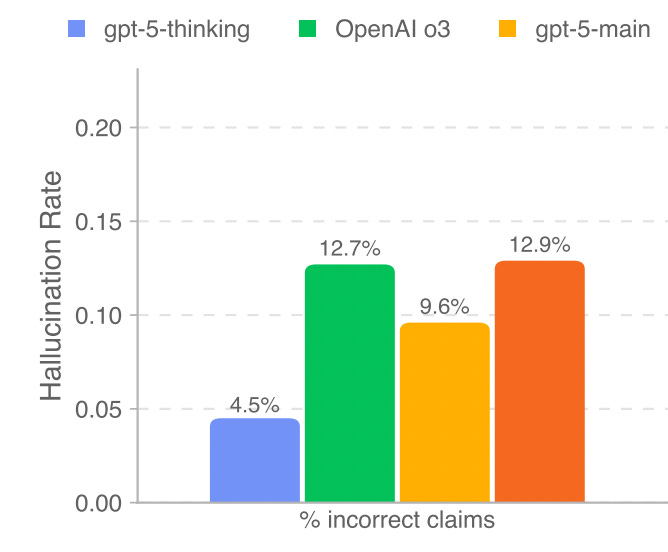

AI is increasingly adept at directly achieving some goals that megapapers help to achieve, such as synthesizing knowledge. AI can also save time that used to be spent copy-editing or identifying ambiguous phrasing in megapapers, as well as suggesting references for you to consider reading. But they can’t do everything that megapapers do, such as conveying intellectual heft and legitimacy, and they are not yet a replacement for real, diverse experts.

Zooming in on part of the figure from the GPT-5 system card, excerpted above. For now, I find the best AI that money can buy very helpful and I’m about to throw this whole thing into a chatbot to help find typos. But none of these systems are yet a full replacement for talking to, or reading the writing of, people who have actually been there and done that.

AI should be used to increase the ambition level that is realistic for a megapaper (e.g., by allowing someone to learn more about a wider array of disciplines), but with humans still being the “system integrators” and evaluators of the knowledge being smashed together, often with help from AI. More generally, I think that changing societal outcome requires changing minds, and the “heft” that comes from many authors with different backgrounds endorsing a certain set of conclusions is hard to replicate with a link to a shared ChatGPT chat. Furthermore, the very process of writing a megapaper is valuable in creating the kinds of tight-knit intellectual communities which are needed not just to summarize the current peaks of knowledge, but also to keep exploring them together over time (it’s not an accident that many of the same names reappear across megapapers).

Conclusion

I’m admittedly a bit biased towards the conclusion that megapapers are important, since I’ve spent thousands of hours on them.

But I also didn’t spend that time for no reason – I gradually built up more and more belief in megapapers and in my ability to execute on them over many years, and constantly learn of new ways in which some of my early megapapers were impactful. It is very rewarding to hear that, e.g., someone read your work early in their career and it helped them wrap their head around a gnarly topic or that it “made the rounds” in a government agency that you really wanted to think about a certain topic.

I am working on a new megapaper right now. I think it’s really important for some people to deeply understand what “frontier AI auditing” means, how it could go well or poorly, what we should learn from related areas like financial auditing and arms control, and what should be done next — but currently, that knowledge is not in anyone’s head (myself included). But soon it could be in millions of heads (or, perhaps more realistically, thousands). That’s worth a lot of hard work, in my opinion, and I’ll get back to it after shipping this and a bit of Netflix.

If there’s a topic like that for you, or another motivation that I discussed above resonates with you — consider kickstarting, contributing to, or helping project-manage a megapaper!

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Larissa Schiavo for feedback on an earlier version of this post, and to everyone with whom I’ve coauthored a megapaper, for teaching me so much.