My recent lecture at Berkeley and a vision for a “CERN for AI”

Merging frontier AI efforts into a single highly secure, safe, and transparent project would have many benefits, and should be explored more seriously than it has been to date.

Author’s note: Yes, this is very long. If you click on the thing on the left-hand side of the screen, it will show you where you are in the article. If you just want the gist of the idea, read “Short version of the plan” and the next three sections after that, stopping right when you get to “Longer version of the plan.” Those four shorter sections will only take about five minutes to read in total.

Introduction

I recently had the honor of giving a guest lecture in Berkeley’s Intro to AI course. The students had a lot of great questions, and I enjoyed this opportunity to organize my thoughts on what students most need to know about AI policy. Thanks so much to Igor Mordatch for inviting me and to Pieter Abbeel and everyone else involved for giving me such a warm welcome!

You can watch the lecture here and find the slides here. While the talk was primarily aimed at an audience that’s more familiar with the technical aspects of AI than the policy aspects, it may be of wider interest.

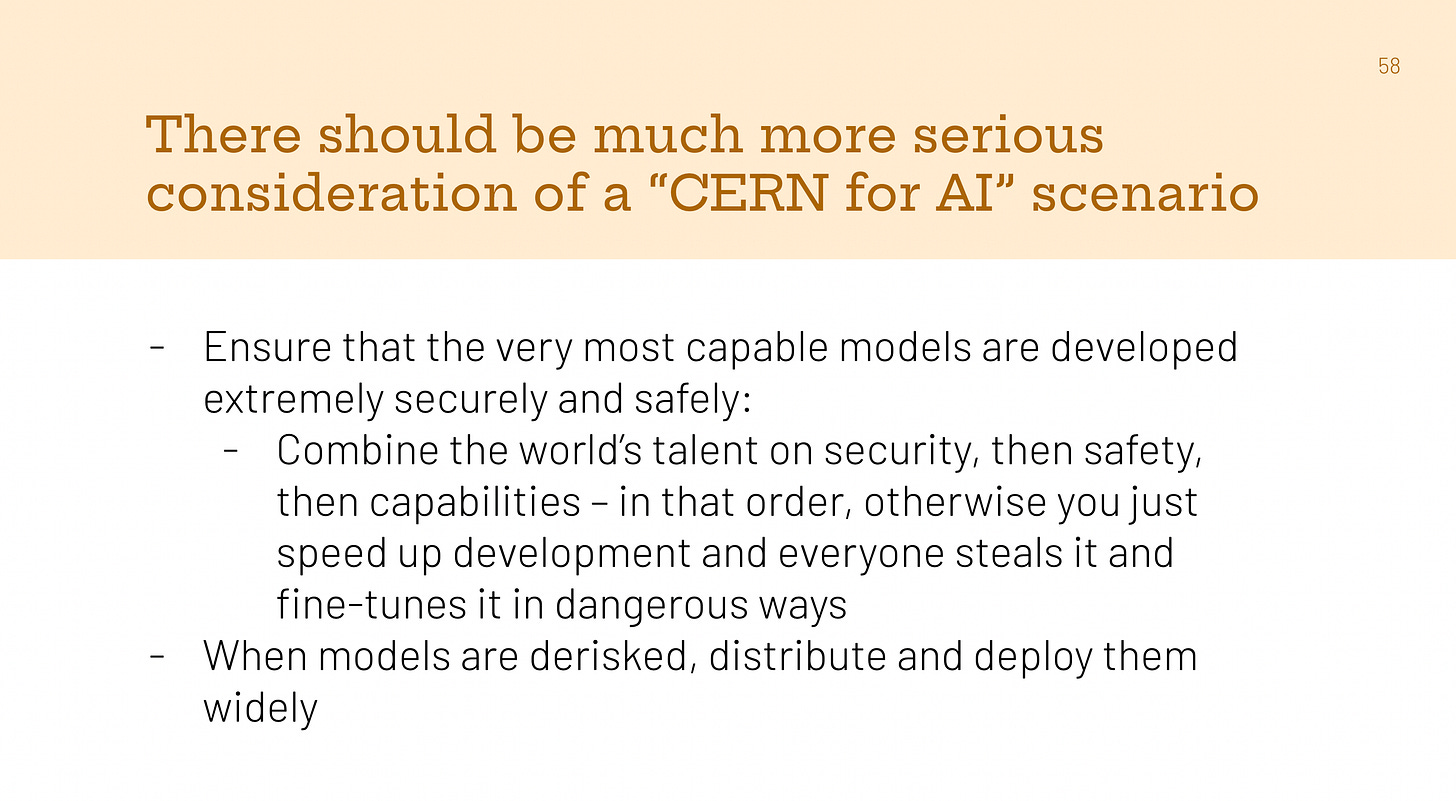

After the talk, I reflected a bit on what I could have done better, and thought of a few small things.1 But the main regret I have with this talk is that I wish I had prepared a more for the section on a “CERN for AI.” The idea behind such a project is to pool many countries’ and companies’ resources into a single (possibly physically decentralized) civilian AI development effort, with the purpose of ensuring that this technology is designed securely, safely, and in the global interest.

In this post, I will go into more detail on why I’m excited about the general idea of a CERN for AI, and I’ll describe one specific version of it that appeals to me. I’ll start with what I actually said in the talk and then go much deeper. I’m not totally sure that this is the right overall plan for frontier AI governance, but I think it deserves serious consideration.

My presentation and the Q+A

Here are the actual slides I presented – most are pretty self-explanatory but I’ll explain the one that isn’t.

Explanation of the slide above: AI development and deployment today are kind of like a world where every building is made by a single person, who doesn’t have all the expertise and time they need to do a good job, and the different people aren’t allowed to team up because it’s illegal to do so, or they don’t trust the other person’s country, etc. Oh, and a bunch of award-winning architects believe that a mistake in the construction process could kill everyone. By contrast, a group of people could build a much better and safer building by combining forces. I made the same basic point with a different metaphor in this blog post, referenced in the slide below. Both metaphors are simplistic, of course.

One of the first questions I got was why this is a controversial idea (I had included it in the “spicy takes” section of my talk). I gave a pretty mediocre answer, e.g., talking about how it could go against some parties’ interests, which was the wrong answer for a few reasons.2 The right answer, in retrospect, is that the biggest blocker to real support and action is the lack of a detailed plan that addresses natural concerns about feasibility, and in particular alignment with corporate and national incentives.

The idea of a “CERN for AI” has a low “policy readiness level.” I’m currently thinking about whether I should start an organization focused on fixing that and a few related issues (e.g., the need for skeptical third parties to be able to verify the safety properties of AI systems without compromising the security of those systems, a key challenge in arms control and other contexts).

Without a well-developed proposal, and with many obvious challenges (discussed below), of course people will be skeptical of something that would be a huge change from the status quo. So below, I’ll give you my own detailed sketch of how and why this could work — hopefully I’ll make at least some progress on policy readiness . I’d love to hear what you think!

One scenario for a “CERN for AI”

Definitions and context

A CERN for AI (as I use the term) would develop AI for global and civilian uses, and over time would become the leading player in developing advanced AI capabilities.

Recall the slightly different definition I used in my slides above:

Pooling resources to build and operate centralized [AI] infrastructure in a transparent way, as a global scientific community, for civilian rather than military purposes.

This is inspired by the actual CERN. See this article for discussion of how the actual CERN works. In short, a bunch of countries built and jointly manage expensive scientific instruments.

In the introduction to this blog post, I used a different (but consistent) definition:

[Pooling] many countries’ and companies’ resources into a single (possibly physically decentralized) civilian AI development effort, with the purpose of ensuring that this technology is designed securely, safely, and in the global interest.

Each definition emphasize different aspects of the idea. I don’t want to spend too much time on these various definitions of the overall concept, since the devil is in the details.

The devil in the details.

There are many things unspecified in my definition, including:

The basic goal(s) of the project;

The number and identity of countries involved;

The incentives provided to different companies/countries to encourage participation;

The institutional/sectoral status of the project (is it literally a government agency? A non-profit organization that governments give money to?);

How big and small decisions are made about the direction of the project;

Whether the initiative starts from scratch as a governmental or intergovernmental project, vs. building on the private industry that already exists;

The extent to which the project consolidates AI development and deployment vs. serving as a complement to what already exists and continues to exist alongside it;

The order of operations among different steps;

How commercialization of the developed IP works;

Etc.

Different choices may lead to very different outcomes, making it hard to reason about all possible “CERNs for AI.” Indeed, I’m not sure if I even want to keep using the term after this post. I currently slightly prefer it over the other term floating around, “Manhattan Project for AI,” which also could refer to various things. There are many other interesting analogies and metaphors, like the International Space Station, Intelsat, ITER, etc. There’s a bit more written about the CERN analogy, as well. I linked to some of the prior writing on this topic in this earlier blog post, and I’d suggest that people interested in a well-rounded sense of the topic check out those links, and especially this one.

I will not aim to exhaustively map all the possibilities here. My goal in this post is just to give a single, reasonably well-specified and reasonably well-motivated scenario. I won’t even fully defend it, but just want to encourage discussion of it and related ideas.

Lastly, I find “a/the CERN for AI” to be a clunky phrase, so I’ll sometimes just say “the collaboration” instead.

Without further ado, I’ll outline one version of a CERN for AI.

Short version of the plan

In my (currently) preferred version of a CERN for AI, an initially small but steadily growing coalition of companies and countries would:

Collaborate on designing and building highly secure chips and datacenters;

Collaborate on accelerating AI safety research and engineering, and agree on a plan for safely scaling AI well beyond human levels of intelligence while preserving alignment with human values;

Safely scale AI well beyond human levels of intelligence while preserving alignment with human values;

Distribute (distilled versions of) this intelligence around the world.

In practice, it won’t be quite this linear, which I’ll return to later, but this sequence of bullets conveys the gist of the idea.

Even shorter version of the plan

I haven’t yet decided how cringe this version is (let me know), but another way of summarizing the basic vision is “The 5-4-5 Plan”:

First achieve level 5 model weight security (which is the highest; see here);

Then figure out how to achieve level 4 AI safety (which is the highest; see here and here).

Then build and distribute the benefits of level 5 AI capabilities (which is the highest; see here).

Meme summary

My various Lord of the Rings references lately might give the wrong impression regarding how into the series I am (I actually only started reading the book recently!). But, I couldn’t resist this one:

The Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring, Wingnut Films.

The plan’s basic motivation and logic

In this section, I’ll give a general intuitive/normative motivation plus two practical motivations for my flavor of CERN for AI, and then justify the sequence of steps.

The intuitive/normative motivation is that superhumanly intelligent AI will be the most important technology ever created, affecting and potentially threatening literally everyone. Since everyone is exposed to the negative externalities created by this technological transition, they also deserve to be compensated for the risks they’re being exposed to, by benefiting from the technology being developed. This suggests that the most dangerous AI should not be developed by a private company making decisions based on profit, or a government pursuing its own national interests, but instead through some sort of cooperative arrangement among all those companies and governments, and this collaboration should be accountable to all of humanity rather than shareholders or citizens of just one country.

The first practical motivation is simply that we don’t yet know how to do all of this safely (keeping AI aligned with human values as it gets more intelligent), and securely (making sure it doesn’t get stolen and then misused in catastrophic ways), and the people good at these things are scattered across many organizations and countries. The best cybersecurity engineer and the best safety research engineer currently only helps one project, and it may not even be the one with the most advanced capabilities. This fact suggests the value of combining expertise across the various currently-competing initiatives. Given the extreme stakes and the amount of work remaining to be done, we should have an “all hands on deck” to ensure that the most capable AI is built safely and securely, rather than splitting efforts.

Different people have different opinions about how hard these safety and security challenges will be, and how much AI will help us solve the challenges we run into along the way. But everyone agrees that we haven’t fully solved either one yet, and that there is a lot remaining to be done. People might reasonably disagree about whether pooling resources will in fact make things go better, but it seems pretty clear to me that we should at least seriously consider the possibility, given the extreme stakes.

The second practical motivation is that consolidating development in one project — one that is far ahead of the others — allows that project to take its time on safety when needed. Currently, there are many competing companies at fairly similar levels of capability, and they keep secrets not just for security’s sake, but to maintain a competitive advantage (which in turn is made difficult by so many people moving back and forth between companies and countries). This creates a very dangerous situation: we don’t know exactly how much safety and capability will trade off in the end, but it’d be strongly preferable to have some breathing room. It’s hard to have such breathing room and to sort out norms on safety and security when everyone is competing intensely and the stakes are high. Having a very clear leader in AI capabilities also limits the potential risks of a small project cutting corners to catch up, since, given a huge lead, small projects couldn’t succeed even if they completely disregarded safety.

The basic logic behind the sequence of steps in my plan is “first things first”: it’s a bad idea to jump straight into pooling insights on AI capabilities and combining forces on computing power before doing the other things. The capabilities that were just advanced will likely get stolen, including by reckless actors. Without a clear plan on safety, things could go sideways very easily as AI capabilities increase dramatically. Therefore, my proposed sequence begins with laying solid foundations before “hitting the gas pedal” on AI capabilities.

The steps in the plan will not be quite as linear as the summaries above imply. There would be value in pilots (e.g., of new safety measures) at each level of AI capability, in negotiating some of the legal and commercial details of pooling capabilities early on, etc. But the step-by-step framing conveys the basic logic, and my view that we should be trying to “frontload” our investments in critical foundations as much as possible.

Longer version of the plan

I’d love to see a super clear, structured, well-justified, etc. version of this plan, or something loosely inspired by it. But my thinking isn’t yet that clear, so this section will be a bit rambly as a result. Still, I hope this section conveys that this not just an abstract idea but a concrete effort that could actually be executed on, step by step, if there were a critical mass of support among some key institutions. Between this and the following sections, I hope to also convey that while there are challenges, for sure, there are also various plausible ways of addressing those challenges.

Note that in this particular section, I will just talk through what happens at each step, assuming that there was an intent among several major players (e.g. companies, governments) to proceed with something like the plan. Of course, that’s a big assumption! We will circle back again on the intent and incentives issues later.

Note also that I’m not at all being comprehensive here about “what I think should be done on AI policy generally,” which includes lots of things that should be done outside of the context of the collaboration (e.g., investing in societal resilience to and adaptation to AI; debates and policy experimentation regarding the future of work; etc.).

Step 1: Collaborate on designing and building highly secure chips and datacenters

AI is a very powerful technology that many people are trying to build and/or want to get their hands on through illicit means. Decisions about who has access to it are very complex and important (see, e.g., the open source debate), but I think almost everyone can agree that these decisions should be decided based on deliberate analysis and informed debate rather than “who can steal better” or “who’s best at tampering with complex machines in order to get their way.” And yet, today’s AI is far from secure and we’re not on track to secure it.

The worst-case scenarios here are quite bad, including the theft of a system that requires extreme care to operate (which is then misused in a catastrophic way), as well as someone “taking over” the project — and thereby possibly even the world — via illicit means. Obviously, these cannot be allowed to happen. Governments and companies should urgently prioritize building the capacity to achieve level 5 weight security as described in RAND’s framework here – even if we don’t end up doing a CERN for AI.

Note that I said “highly secure chips and datacenters” above for simplicity, but there are other relevant aspects of security as well (e.g. secure communications between different locations). And I mean security in a broad sense, including not just avoidance of theft by third parties but also avoidance of tampering/sabotage, leaking, and unauthorized use of the technology being built.

Several possible concrete actions suggest themselves, given the above:

Government incentives or requirements to make chips more secure. Today, there are tradeoffs between making GPUs/TPUs cheap and making them secure. There are some early efforts toward making chips “hack-proof,” such as confidential computing features, but these are generally considered impractical today for the purposes of frontier AI systems. You can’t fit a “production-size” neural network into the special parts of these chips that are harder to steal from. Many companies would love for practical confidential computing to be an option, but individually they have limited bargaining power vis-a-vis NVIDIA et al. given that everyone is begging for chips. So ensuring that these kinds of features are made standard ASAP will likely require a push from governments.

Joint research and development on external chip security features. Besides the internals of chips, there are many other things to consider that could make it harder for chips to be tampered with, smuggled, etc. These include location trackers, flexHEGs, tamper-proof unique IDs, etc. – none of which, to my knowledge, is a major priority of governments and industry today, but could be. Making these mature and standard features of chips would expand the range of possible projects/deals/agreements etc. that could be negotiated, including something like a CERN for AI. Notably, this could actually benefit the NVIDIAs of the world in the long run. Right now, the two options for selling top-of-the-line American chips to untrusted countries are “you sell the chips and get the buyer to sign some document saying they won’t misuse them, but you don’t really know what happens after that” or “you can’t sell them at all, and make less money as a result.” Better security features could open up more flexible possibilities.

Joint research and development on secure datacenter designs. Today, there are basically two kinds of AI datacenters: insecure big ones, and secure small ones. The biggest AI datacenters are not air-gapped, don’t have super rigorous physical security, etc. Conversely, secure government datacenters are presumably much smaller than the tens-of-billion dollar private sector datacenters, judging by the lack of large gaps in known revenue sources for NVIDIA, and the lack of huge line items in defense budgets. Getting to the best of both worlds here – large scale and high security – will require collaboration across organizations and sectors.

Pooling of resources to actually build secure datacenters. Given strong foundations in the areas above, you then need to actually build these huge, secure datacenters with secure chips inside them. This will require a lot of energy, special construction requirements, etc., as well as a thoughtful approach to transparency (see discussion below). This may benefit from, e.g., being structured as a joint venture among companies who might benefit from economies of scale (e.g. sharing government-provided power and physical security but having separate chips set aside for each of them internally).

Piloting of internal segmentation. Compute will be a key part of the collaboration’s “moat” eventually, as will engineering talent, and the ability to protect weights. But there is another factor that needs to be considered in order to maintain an advantage over “rogue projects” outside of the collaboration, namely some sort of segmentation of different algorithmic secrets. If all algorithmic innovations (including those related to pre-training, reinforcement learning, inference efficiency, etc.) are known to everyone in the collaboration, then it will be easier for rogue projects to keep up (especially to the extent compute is not well-controlled). Thus, there might be a need for segmenting the insights learned about different aspects of the project, so that the “blast radius” of any particular leaker, defector, etc. is limited. This would pose cultural challenges, and it may turn out to be the case that this is a bridge too far – e.g., if too much segmentation makes it impossible to build external trust (discussed more below). In that case, perhaps we need to rely on the compute moat. But I think segmentation should at least be “piloted” since, depending on various factors such as relative compute access, etc. it may turn out to be critical for addressing the problem of rogue projects outside the scope of the collaboration, which I’ll return to in a later section.

Regular red teaming / penetration testing. In order for any of this to actually be trusted, you need to adversarially test it regularly and at scale. If the US government were centrally involved in some of these early steps, for example, the NSA might regularly test the collaboration’s defenses at various levels (chips, datacenters, and specific AI projects/organizations using those chips). There is a fine line between government involvement that improves security in service of widely shared global goals, and government involvement that gives the impression, or creates the reality, of capture by the national security state. Striking this balance will not be easy, but I don’t see a better way to have a truly secure CERN for AI than to have governments closely involved.

Investment in and transparency about organizational culture and integrity. The collaboration should have very clear norms around internal sharing of information, even if those include some segmentation. For example, it should be very clear who has the ability to know and who has the ability to change model behavior (i.e., “the AI’s goals”). There should be robust investment in whistleblowing processes. The world should have high confidence that if there is ever a false claim made by organizational leadership about any aspect of the systems being built there — such as who has access to what and who can do what with the technology — that claim will be quickly disproved by personnel who know better. The world should also know that any security or integrity incidents will be thoroughly investigated (e.g., it will be determined whether the mistake was based on poor information sharing internally or if there was an intent to deceive), and that the leader(s) will be removed and replaced if needed.

Note that keeping the weights of an AI be secret is the same thing as having them be secure (in the sense of preventing theft), since they are just a list of numbers, but having the collaboration as a whole be secret is not the same as the project being secure in a general sense. In most contexts, “security through obscurity” is a bad strategy, and the project should not be overly secretive. Excessive secrecy is likely to not only make this step ineffective (due to insufficient technical input on and criticism of the design process) but also to exacerbate the competitive pressures which the project is intended to help address. I would love to see a crash effort on security that is explicitly and publicly intended to pave the way for a longer-term project like a CERN for AI, rather than a more secretive project that could be (accurately or inaccurately) interpreted as an attempt to race ahead of other companies and countries.

Success for this step of the project – which won’t literally be completed before anything else happens, but should be frontloaded as much as possible – will mean that the world can have very high confidence that model weights trained at the datacenter or datacenters involved cannot be removed without a highly visible series of decisions with many people involved, and thus cannot be done illicitly. More generally, the world should have confidence in the decision-making process of the organization, and know the project’s technology cannot be secretly misused by any organizations involved.

Step 2: Collaborate on accelerating AI safety research and engineering, and agree on a plan for safely scaling well beyond human levels of intelligence while preserving alignment with human values

As with the step above, this step involves pooling resources to solve a very difficult problem. There are two distinct goals for this step, which are complementary: speeding up AI safety research and engineering, and arriving at a joint plan for the scaling process in the next step. That is, we want to better understand the conditions under which AI will be reliable, aligned with human values, etc., and we also want to hash out a set of milestones, principles, risk thresholds, etc. for ensuring that those properties are maintained as AI capabilities advance in the next step.

Several investments could be made during this step of the project:

Mutual red teaming among companies. Currently, companies contract with private individuals and small non-profits/companies to red team their AI systems, and also do some red teaming internally. They do not generally give access to competitors, other than what happens naturally when the product becomes available to everyone. This should change by step 2: regardless of which AI company you are at, some of the best experts are at other AI companies, and the safety of what you’re building should benefit from their expertise.

Scaling up and supervising automated safety researchers/engineers. Existing AI capabilities can be applied, at large scale, to speed up safety research. Supervising these increasingly capable automated safety researchers/engineers will also give valuable practice for step 3.

Scaling interpretability research in a secure setting. Currently, AI interpretability research – which might be a critical foundation of getting solid safety guarantees for advanced AI systems – is either done on open source models that are a bit behind the state-of-the-art, or it is done internally at companies using state-of-the-art AIs. It’s not trivial to allow the global scientific community to do interpretability research on the very most capable AI systems without open sourcing them, but with a concerted effort, the CERN for AI could do exactly that. This could be done via specially designed APIs, on-site research, or some combination thereof. While this could be done today to an extent, the importance of it would grow dramatically in a CERN for AI scenario, since there would be a very clear set of AI systems that constitute “the frontier” and a huge amount of interest in understanding them. There could also be a lot more joint investment in sorting out the logistical issues involved.

Large-scale automated red teaming. The computing power aggregated together for the collaboration could also be applied towards AIs red teaming other AIs. This is done today, but could be scaled up more with less competitive pressure to get things out the door quickly, and with more collaboration among safety teams to make it work well.

Refinement of a joint responsible scaling policy and safety case plan:.There are many common elements in the policies for scaling up AI safely that have been published by frontier AI companies. During step 2, they would hash out the differences among them and align on one that is “ready for prime time” in step 3.

Expert/government/public discussion on safety risk tolerances. It would be valuable at this step to solicit expert, government, and public input on appropriate risk tolerances when scaling up AI in step 3. That is, given that everyone will or could be affected if things go wrong, as well as if they go right, there should be broad input into how speed and caution should be balanced. Should we accept, for example, a 1 in 1,000,000 chance of a catastrophe in order to reach the next tier of AI capability, given certain assumptions about the benefits that might come along with success, and what constitutes a sufficiently rigorous risk estimate for such purposes? This raises a combination of technical and normative questions that should be discussed in the open rather than decided behind closed doors with limited discussion.

During this step, it will be important to leverage the security obtained in step 1 in order to engage with the global scientific community on the safety properties of increasingly capable AI systems. It would also make sense at this stage to have various societally beneficial “spinoffs” (loosely defined) – AI capabilities that could be commercialized, as well as scientific breakthroughs that could be published for global use, which came about during steps 1 and 2 but before capabilities were fully scaled up in step 3. This could help ensure political buy-in for the project, enabling people to get value along the way rather than waiting until the very end.

This combining of forces on safety capabilities – with everyone checking everyone’s homework – will create some soft pressure to consolidate capabilities as preparations begin for the next phase, since some architectures/training approaches/teams etc. will be better equipped to “handle the heat.” The stage will thus be set for step 3.

Step 3: Safely scale AI well beyond human levels of intelligence while preserving alignment with human values

In the previous steps, there was some progress in AI capabilities occurring, but the focus of the collaboration was on laying security and safety foundations. During step 3, building on those foundations, there is a shift towards pooling resources to advance capabilities.

The resources pooled could include some combination of computing power (e.g., distributing certain training runs over multiple datacenters in the collaboration), bringing more engineering talent to certain scaling efforts, and/or combining previously siloed algorithmic secrets into a single project. This is the most dangerous step if not done carefully, though I think that even a relatively reckless version of this may be safer than the default scenario of scaling happening without much of a concerted effort to prepare.

It’s worth briefly questioning the premise of whether there will really be an uptick in AI capability progress at this step. After all, progress is rapid already today even without pooling resources, and in the discussion of steps 1 and 2, we didn’t talk about any efforts to stop that. Nevertheless, I think that there will (and assuming safety and security efforts are proceeding smoothly, probably should) be an acceleration at this step. This is true for a few reasons.

Compute that was previously allocated towards automated safety research can start to be reallocated towards automated capability research and to training and inference for frontier models.

Frontier AI companies (let alone individual projects within those companies) currently have much less than a majority of relevant compute, so pooling resources into a single project could substantially increase the capabilities of the scaled-up project (though the increase may be less than the factor by which compute is increased).

Publications of new capabilities at one company seem to somewhat frequently surprise those at other companies, suggesting that the algorithmic insights learned by each company are only partially overlapping – and therefore there can be gains from combining them.

So, while AI capability advances were likely not frozen at the beginning of step 3 by any means, there will probably still be a lot of “gas in the tank” to scale things up further.

Picking the system(s) to scale up will not be trivial, but this step can leverage analytical frameworks for safety designed in step 2.

As scaling up progresses, there will need to be milestones along the way, such as those used in current scaling policies (e.g., testing rigorously every time compute is scaled up X times, or capabilities increase by Y amount). Indeed, the whole idea of consolidating capabilities in this way was to be extra careful, and this extra caution should have begun in step 2 already. The shift during step 3 will be bringing everyone’s capability, safety, and security talents to bear on a specific system or small number of systems (since not everything can be scaled up).

At the end of this process, AI capabilities will have been significantly advanced. They may not have completely stopped advancing (since for any qualitative level of intelligence that can be achieved, there seems to always be some possibility of speeding it up, producing more copies of it, etc.). But the collaboration will have likely achieved highly transformative capabilities. Just how capable AI will be at this step is hard to say, but I expect it will, at least, be able to outperform any human organization on any well-specified task performable on computers (which is why frontloading security and safety was so critical). Among other things, this will likely unlock a massive wave of scientific and technological innovation in areas beyond AI such as medicine, materials science, etc., and make possible very significant economic transformations as a result.

To reiterate, I am framing all of this in terms of discrete steps but in practice, some degree of publishing of results, distribution of model weights, solving of hard technical scientific problems via AI and sharing the results with the world, etc. will have already occurred. But now this distribution of AI and its benefits will be the main focus.

Step 4: Distribute (distilled versions of) this intelligence around the world

In order for the technology developed in this collaboration to benefit everyone, either direct access will need to be provided to everyone, or there will need to be some indirect path to benefit (e.g., via the AI being used to solve problems in medicine and sharing the results).

This step is in some respects the most complex since it involves complex questions of risk mitigation, balance of power among AIs distributed around the world, etc. At the same time, this step will also benefit from the advice of superhumanly intelligent, human-aligned AI. And as the step that’s furthest in the future, it’s also the hardest to predict, but nevertheless I’ll offer a few comments on what might happen in step 4:

Direct solving of hard problems by the most capable AI. It will now be possible to directly apply AI to solving many hard problems — specifically problems which are by nature amenable to technological fixes (which is not all problems). AI may also be applied in ways that help indirectly solve problems which aren’t directly amenable to a technical solution, problems, by creating the technological building blocks of economic growth, abundance, etc. For example, climate change is not strictly a technological problem but by reducing the costs of ambient carbon capture, AI could simplify the politics of it.

Remote access to the most capable AI for solving local/national/regional problems. It will not be realistic, or ethical, for the collaboration to try to anticipate all the problems that need to be solved in the world. There should be some degree of direct (perhaps rate-limited) global access provided to the most capable AIs, so that various parties can solve their own problems. Whereas the bullet above refers to global challenges of wide interest to many stakeholders, in this bullet I’m referring to problems that may be smaller in scale, or to global challenges that are of special importance to those in certain parts of the world.

Remote access to (weaker versions of) the most capable AI. Using the same infrastructure that was developed to provide global access to the most capable AI, it may also be possible to provide more permissive access to weaker versions of the AI. This might be, e.g., smaller versions, or distilled versions, or versions with less test-time compute applied per answer, etc.

(Weaker) models distributed to secure datacenters. Using some of the same technology required in earlier steps, or perhaps using new innovations created by the AI that has become newly available at this step, it should be possible to provide “secure-datacenters-in-a-box” and other solutions to distributed access. This is particularly applicable to solving problems that require low latency.

Open sourcing of (weaker) models. Lastly, there is full open sourcing of models. This is the strongest kind of wide access since it cannot be undone, but also brings with it the most risk of abuse. Perhaps with the help of broadly superhuman AI (e.g., making society more resilient, thoughtfully designing checks and balances, etc.), we would be able to provide direct access to the weights of the most capable AI to everyone by open sourcing it— it’s hard to say today, hence I put “weaker” in parenthesis to allow for both possibilities.

(Note that I am intentionally being vague about which technology is released freely as a public good, vs. which is commercialized by companies involved in generating that intellectual property, which is released freely and then commercialized by many parties, etc. How commercialization works in the context of a collaboration like this is a key question. I have some vague initial thoughts, but I ran out of steam after 10,000 words or so and want to get this out the door. I leave this question an exercise to the reader. :) )

Rather than prejudging all the details of every step above today, I think it is more important to build a good foundation of accountable decision-making processes. In addition to drawing on strategic input from the AI at this step, there will of course be decisions that people and governments need to make, and it will be critical not to centralize power in any set of human or AI “hands.” We turn to this challenge next, which cuts across all the steps of the collaboration.

Decentralized decision-making over centralized capabilities

One way in which the idea above could not just fail but also make things much worse worse is if it concentrates power in a harmful way. To be clear, as mentioned in the lecture linked above, I think AI already poses a high risk of concentrating power. But by consolidating capabilities, a CERN for AI (if poorly designed, at least) could make the situation much worse.

My view is that we should not conflate — and we should try very hard to separate — the physical and institutional location of AI capabilities, on the one hand, and the distribution of power over those capabilities, on the other. There are good reasons to consolidate capabilities, and also good reasons to distribute power – so perhaps we should just do both simultaneously.

There is a lot of precedent for consolidated development of a certain technology, while maintaining wide input over that technology – indeed, that’s exactly what CERN is! There are countless other examples, too, such as electricity infrastructure, where precisely because utilities tend towards a monopoly, governments put various constraints on what they have to do, e.g. related to providing wide access. Clearly, efforts to “square the circle” of distributed input over centralized capabilities don’t always succeed. But some of them do, and the problem of corner-cutting on security and safety is so severe that I think we may just have to give it our best shot.

A few illustrative ideas of how this might work include:

Get government and direct public input on the rules determining AI behavior.

Get government and direct public input on risk tolerances for scaling up AI (see safety section above).

Require more extensive sign-off from a wider range of stakeholders on higher-stakes decisions (consider, by analogy, the requirement to have states vote to ratify changes to the US constitution).

Which decisions should require consensus, majority vote, etc. would have to be carefully considered in designing the organization. You would not want to design it in such a way that a company or country which has a secret AI project can abuse their voting power to slow down the collaboration and buy time to catch up. Perhaps this for this sort of reason, and to prove that this is truly a globally-minded rather than parochial project, some decisions should be made by people chosen via random selection, so that they don’t have any “skin in the game” besides having an interest in humanity continuing to thrive.

Responses to objections

What’s the plan on military uses of AI?

I’m not sure – this is one of the hardest parts, and it’s one of the things I’m most unsure about. But here are a few lines of thinking to consider in further analysis of my proposal:

A CERN for AI could be just one part of a larger strategy, and in parallel, you might also negotiate arms control agreements for non-frontier AI (e.g., on lethal autonomous weapons). In this scenario, there is still some military AI but it is not totally destabilizing – there are ground rules. Notably, those ground rules are starting to be developed (though they’re still early). This doesn’t address the possibility of secret frontier AI projects, which is addressed separately below.

The tech developed by the project could help here, by enabling easier enforcement of agreements (e.g., privacy-preserving surveillance could be used for detecting violations of arms control agreements and undisclosed compute production).

Perhaps we should actually not exclude military projects from the collaboration at all. I defined military capabilities as outside of the project above, since I’m drawing inspiration from CERN and worry about unsafe militarization of AI. But you could plausibly have have a public-private partnership that is in some ways analogous to CERN but with some major differences such as including military projects. What this would look like is unclear, but, e.g., you might allow defensively-oriented military development to be conducted as part of the project, and these capabilities might even be proactively spread around the world to make it harder for anyone to gain an offensive advantage in any region. Whether this would make sense at all, and whether it’d be feasible to implement in practice, depends on many factors that I won’t get into here.

Won’t this just be a huge, ineffective bureaucracy?

It could be! Domestic government agencies, international organizations, and nonprofits (three types of legal status that this entity might have) are all prone to this failure mode.

The solution will depend on the details of which specific bureaucratic failure mode we’re trying to prevent. Care would need to be taken in designing the incentives of key decision-makers at the collaboration. If some kind of formal voting rules are used (e.g., countries’ representatives voting on certain decisions), it will be important to avoid baking in too much of a “lowest-common denominator” tendency. On the one hand, some risk aversion and consensus orientation is desirable and part of the point, but this can go too far and result in total ineffectiveness.

Another key consideration is which responsibilities the entity should take on, vs. responsibilities that should be left to other entities. I don’t envision a CERN for AI trying to entirely replace existing institutions like private companies, but rather leveraging their strengths and complementing them in some way. If the collaboration has no hopes of (e.g.) building better chips than private actors, it shouldn’t try in the first place.

Overall, I think that this is a serious concern (though as with all of my concerns, I think we also need to consider the risks of the current plan for AI governance, or lack thereof).

To some extent, bureaucratic overreach can be addressed with careful design and learning from (and leaning on) the most effective institutions. But there also needs to be a serious discussion, before going down this road, of what happens if the effort does succumb to this or another failure mode. How could the collaboration be wound down gracefully?

Why and how would countries with different goals agree to this?

There are several reasons why countries might agree to something like this, some of which overlap with the reasons companies might participate, which I’ll discuss below and therefore skip here. Country-specific reasons include:

Reducing exposure to attack and the costs of competition. While a poorly designed CERN for AI could pose a security threat to some countries (e.g., developing advanced capabilities that are then stolen and misused), a well-designed CERN for AI could represent an improvement over the status quo in two ways. It could provide a pathway to gradually reducing the threat posed by adversary’s military AI capabilities, insofar as these adversary capabilities will begin to decline as a fraction of global AI capacity; and a collaboration could reduce the need to invest in costly military AI capabilities, given the reduced threat.

Gaining access to advanced AI capabilities. Developing countries might worry, reasonably, about being “shut out” of the benefits of AI by default. They might fear that a CERN for AI could make things worse, though it could also make things better depending on the details. In order to ensure wide and successful participation, it would therefore be critical for there to be a serious commitment to benefit distribution, so as not just to allay concerns but to create a strong positive incentive to participate.

Currying favor with other countries. Country A may benefit in terms of its relationship with Country B by joining the project sooner rather than later, and thereby demonstrating loyalty, collaborativeness, etc.

Shaping the governance of the project and the AI applications pursued. As the expression goes, “if you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu.” Some companies and countries may not think CERN for AI is the absolute best case scenario for them, but may nevertheless want to shape how it is conducted. To be clear, I think we shouldn’t do something like this unless there is a genuine intent and serious effort to ensure the collaboration benefits everyone, even those who aren’t involved (most importantly, by avoiding catastrophic harm to them). But different organizations will have different specific priorities and visions for how the collaboration should work, and that may inform whether and how they want to get involved.

To be clear, I think the above are important points but there are also very legitimate reasons for skepticism, including, not exhaustively, a very low/non-existent level of trust between some countries such as the US and China. At the same time, you can’t ignore those countries, either, and my points about why you’d do any of this still stand. We would have a better sense of what exactly is possible after more investment in areas like verification of possible agreements on AI, more analysis of different variants of the CERN for AI approach, etc.

Why and how would companies with different goals agree to this?

Whether participation in, and advocacy for, a CERN for AI benefits individual companies will depend on the details of the collaboration. A few ways in which a CERN for AI could be in companies’ interests include:

Seeing it as the most satisfactory solution to growing government concerns about safety and security. That is, by leveraging government investment and pooling lessons across companies, each individual company might protect itself from being regulated out of existence or nationalized, which could be the default course if the industry as a whole and individual companies in it come to be seen as reckless (e.g., if capabilities advance faster than security and safety).

Seeing it as a source of revenue. While it’s not totally clear how much “CERN proper” might be a customer of chips directly, vs. being an umbrella organization for a bunch of companies and governments that themselves are buying chips, either way, it’s plausible that governments “waking up” on AI could lead to revenue for some parties. NVIDIA, for example, might conclude that under this vision, there are ample opportunities for sales that might otherwise have been foreclosed by the ratcheting up of export controls and the growing effects of regulation. Additionally, energy providers, construction contractors excited to build the world’s largest SCIFs, etc. might be quite interested in the opportunities here.

Leadership opportunities for individuals and organizations. Companies and people within them may benefit in terms of prestige, resources tapped into, etc. by being centrally involved in a collaboration of this kind. Companies may be elevated first to the status of “national champions” and then “international champions” of a highly prestigious global initiative.

Just thinking that it’s a good idea. Commercial incentives are important but are not everything, and there is ample precedent for companies stepping up in times of need (wars, pandemics, etc.). I think that as the stakes of AI become increasingly clear, many will see it as their patriotic duty and/or their duty as a citizen of the world to advocate for the policies they think will actually be effective in mitigating risks from AI, and they might conclude that this is the right approach.

How would you get started?

First, there needs to be a more robust discussion of the possibilities. I’m hopeful that, with recent discussion of “Manhattan Projects for AI,” and so many things changing anyway with the Trump administration, that will happen in the coming months.

But then what? I think one possible way to bootstrap a CERN for AI is to combine two powerful strategies: iteration and conditional commitments:

Iteration: Via tit for tat or some other kind of iterative back and forth, different parties can gradually ratchet up their involvement. In this way, the project can gradually grow to become the leading effort: company A might allocate 1% of its compute, then company B might allocate 1%, then company A allocates 3%, and so on. If the process is designed well, there will be no single moment at which someone is creating a major (commercial or military) risk to themselves.

Conditional commitments: Using an assurance contract (where obligations kick in only when a certain threshold of participation in the contract has been reached), or something similar (as is often done with treaties), it may be possible to assure companies and countries that they will not be “going out on a limb.” This can be combined with iteration.

Which countries would be involved exactly?

The hope is that all of them would be involved eventually. The US would need to be involved early on, and in my ideal world it would lead the effort from the beginning. There are two reasons I say this, besides being an American. First, the US is the leading country in the world in AI and more generally, and therefore is best positioned to make this happen; and second, this style of US leadership seems preferable to me over other possible styles of US leadership (i.e., a more militarily oriented project).

Participation from the rest of Five Eyes seems important in order to get solid security-related cooperation in the first step. It would also be important to have the early involvement of other countries that are integral to the semiconductor supply chain such as Japan, South Korea, and The Netherlands. Some kind of partnership with the EU also seems important.

The China question is critical, and can’t be postponed for too long in the lifecycle of the collaboration — both because of China’s strong position in AI and because of Taiwan’s key role in the semiconductor supply chain. The US would of course be skeptical of China’s involvement, and vice versa. But recall that secrecy on most aspects of the project is not essential (and may be harmful), and that more generally, there are many shared interests at stake here, most notably the avoidance of catastrophic risks from AI. So I think that if step 1 is executed effectively and transparently, there is a serious possibility of both countries being involved.

What about rogue projects generally (and China specifically) leapfrogging the collaboration?

Many if not most smaller/slower AI chips, projects, companies, datacenters, models, etc. would likely be out of scope of the collaboration. Thus would not be considered “rogue,” but just separate from what CERN for AI is addressing, which is the very most capable AI systems. But what about efforts to build actual frontier AI that competes with or even surpasses the capabilities in the collaboration?

Depending on how far along things are, competing with the collaboration may or may not be illegal, frowned upon, etc. For example, early in the process of building the coalition designing and executing on the collaboration, some countries may not have opted to participate, and there may be no international law saying they have to cease frontier AI development. In that case, countries in the collaboration will do what they’re already doing for general AI competition purposes, namely using surveillance, espionage, etc. to keep track of those outside the collaboration.

There are two distinct issues here, which have different outlooks: there’s the question of how much compute China (or another country outside of the collaboration) can produce or acquire, and then there’s the question of how efficiently they can use it to develop AI capabilities.

Today, compute is an area where the West has a big (though shrinking) technological advantage over China, and China is close behind on algorithms and engineering skill. But this could reverse in a CERN-for-AI-but-without-China scenario. On the current trajectory, ignoring CERN for AI as a factor, China is rapidly building a self-sufficient compute supply chain, and several years from now, it may be more directly competitive with the West (this is speculative and depends on many factors). Let’s assume that that trajectory continues.

By contrast, assuming some degree of segmentation (discussed above in the security section), the collaboration will be a “sponge” for algorithmic insights from around the world, but would only let some of those insights leak back out. China, by contrast, would be drawing (directly) on a more limited pool of talent, plus what it can steal from the collaboration. So even assuming compute parity (which is a big assumption, as right now China is well behind in overall compute volume and technological sophistication), it may turn out that that the collaboration’s compute goes farther via all of the engineering talent at its disposal.

The CERN for AI project will also have access to very sophisticated AI which can help aid in analyzing open source information to detect signs of rogue projects (e.g., suspicious patterns of non-publication among some scientists), data regarding compute sales, etc. and could provide some of its technology to intelligence services, as well, to the extent that this is feasible without compromising the geopolitical neutrality of the collaboration in the eyes of participants.

Lastly, it’s worth noting that US-China competition is a known tricky issue in any scenario, with or without a CERN for AI, so hopefully you will not judge me too harshly for not having solved it in these few paragraphs.

Isn’t this a CERN for AGI, not AI?

I don’t love the term AGI, since I think that it creates more of a sense of a “before/after AGI” binary than is actually the case. I think things are smoother than that. So here, I use the term AI to refer to the full range of possible capabilities, including what some would call AGI.

What about other aspects of AI safety beyond the model itself?

It may turn out that simply designing AI models in a safe way within “the perimeter” of the collaboration does not suffice to allow those models to be widely distributed. For example, perhaps they can be fine-tuned to be more harmful once on the outside, or perhaps deploying them responsibly requires other “layers of defense” such as content filters, monitoring for abuse, etc. It’s hard to say how acute this problem will be, but it might turn out to be very acute if it proves intractable to separate out “dangerous knowledge” like the ability to generate new bioweapons from general knowledge of biology and the ability to use the Internet and to reason.

To address this issue, you could include non-model safety interventions in the scope of what’s required before distributing model weights around the world, although that runs the risk of being very paternalistic, authoritarian, etc. and I’d generally prefer that the CERN for AI narrow its scope and ambitions as much as possible. Still, this topic merits more analysis. Another line of thinking is that there should be significant investment — supercharged by the capabilities created in the collaboration — to build build societal resilience, so that even if models are deployed in harmful ways, the impacts aren’t catastrophic.

What about anti-trust?

I’m not a lawyer, but I suspect that there would need to be some kind of special permission granted by the government(s) in order to do at least some of these things, since there is no safety exception for anti-trust (see also here).

How does this compare to a “Manhattan Project for AI”?

It depends what you meant by that term. As with CERN for AI, “Manhattan Project for A(G)I” doesn’t have a consensus definition. Different versions of one of these may be more or less similar to different versions of the other. E.g., rarely do people using the term seem to imagine quite the degree of secrecy that was involved in the actual Manhattan Project, given that the term is sometimes used in public reports.

Still, broadly speaking, it seems that there are some similarities between these ideas, in that both likely involve significant public-private collaboration related to AI safety and security. There is a different in emphasis, and likely many differences in the details in implementation. Whereas Manhattan Project connotes national objectives, CERN connotes global objectives. Whereas Manhattan Project connotes military use cases, CERN connotes civilian use cases. The extent of involvement of different countries may vary a lot, as well.

I think there is likely a lot of convergence in some of the steps involved in each, such as on security. As noted above, I think any serious effort at AI governance requires significant frontloaded investment in security.

Again, depending on the details, it may be that the differences are greater or smaller. If I were to see a detailed proposal for a Manhattan Project for AI, I’d have more of an opinion on how it compares.

You talked a lot about the US, but won’t the US want to go it alone under Trump?

My sense is that there’s still a lot of uncertainty about what the Trump administration will do on AI. It seems like different people involved have different opinions, and the average/official/most senior view may change over time as the facts on the ground evolve. That being said, I would remind people that Trump seems to like striking deals, and this could be the most important deal in history.

Aren’t lower levels of AI important also? How would those be regulated in this scenario?

Yes, they’re also important. Similarly to how there is starting to be “tiered” governance of different kinds of systems (e.g., based on the compute involved in their training), the CERN for AI would focus exclusively on the very most capable AI systems, so lower level AIs are out of scope here.

Isn’t this an all or nothing idea, and therefore fragile and/or unlikely to happen?

I don’t think it’s all or nothing. It could be that even with only a small number of companies and countries, you could still accomplish a great deal on security, safety, and capabilities and end up better off in some ways than without doing the collaboration at all. There may also be degrees of involvement, such as “observer status” or similar, such that from the perspective of a country or company, you don’t have to decide between going all-in and not participating at all.

Won’t algorithmic breakthroughs render any CERN for AI irrelevant?

One might say something like: “given that algorithmic progress plus some compute will continue outside the project, and some of it will be published by the project or leak out, there’s no point in doing the project — the remaining compute outside the collaboration could be used to do a lot of harm.”

This gets to the question of absolute vs. relative capabilities – perhaps there is some absolute level of AI capability that, if reached, could lead to catastrophe. Or, perhaps not, and what matters is relative capabilities, in which case this objection doesn’t land — unless (in my view implausibly) there is such a massive algorithmic breakthrough outside the collaboration that not only is it not something already discovered within the project, but also it is greater than the difference in relative compute plus the algorithmic secrets which the project has and outsiders don’t. Recall that not just compute but also research and engineering talent would be pooled in the CERN for AI scenario.

This point merits more analysis, since it’s hard to rule out the “absolute capability is the key thing” possibility. I suspect that some absolute capabilities (e.g., the ability to synthesize new bioweapons) are risky regardless of how much AI is applied to defend against it, but I also think that non-AI defenses could be helpful here (e.g., physical defenses against biological threats).

Overall, while this is a subtle issue, I personally find it very unlikely that relative compute will ever not matter at all. Even if we get much more efficient with AI, it will still be better to have more compute than less compute. And insofar as there is a concern about a dangerous absolute level of capability, then it is important to leverage the capabilities inside the collaboration to help safeguard society against those risks.

Isn’t this just the Baruch Plan but for AI instead of nuclear energy, and if so, why wouldn't it fail like that did?

It’s a lot like the Baruch Plan in that it calls for (some) consolidation of development of a critical technology, and it might also fail like the Baruch Plan. I think it’s premature to conclude one way or the other but certainly we should learn from history.

(Note that I say “some” consolidation because the Baruch Plan would have either directly controlled or had the ability to inspect all nuclear fission but my proposal focuses only on frontier AI, not all AI. Note also that there is an organization calling for a “Baruch Plan for AI” but I have many disagreements with their proposal.)

There are a few differences between AI and nuclear energy. In the case of AI, the technology is currently “born” private (i.e. in companies) rather than being born in governments, let alone militaries, as with the Manhattan Project. This creates a different set of stakeholders, incentives, mindsets, etc. I am a big believer in the importance of framing and path dependencies, hence why I use CERN for AI rather than Manhattan Project for AI, and I think that starting AI on a different and better foot than nuclear weapons may lead to different outcomes than what happened with nuclear energy.

Additionally, despite popular belief based on the easy copying of data and algorithms, the AI supply chain is highly concentrated in many respects, especially the equipment used to build the machines that make the chips. The company ASML in The Netherlands, for example, is the only provider of a very important $100 million machine which is in some respects the most complex tool on earth, and my rough understanding is that there is more than one possible providers of every component of the nuclear weapon supply chain. China is of course rapidly trying to recreate the extremely complex semiconductor supply chain, but it has not fully succeeded yet. By contrast, North Korea built nuclear weapons on a (comparative) shoestring budget.

Those points aside, I think this is a really great question and I would like to see more analysis of the similarities and differences between these cases.

What if you don’t solve safety in time to meet the agreed-upon risk tolerance?

In this scenario, the capabilities under jurisdiction of the collaboration could slow down for a bit after or during step 2, or mid-way through step 3. It would be much easier to do this in a CERN world than a non-CERN world, given the breathing room that’s been created.

There may be some upper limit on how long and how much the collaboration could slow down, with this limit being set by the quantity and competence of companies/countries outside of the scope of the collaboration (which may be known, via surveillance or public announcements, or may be hypothesized but unconfirmed, from the perspective of the collaboration). So I don’t think the CERN for AI idea is on its own a sufficient solution to this concern, but I think it would position things better than not doing it at all, assuming good execution.

Also, there are likely to be many ways of productively and safely using all the compute and engineering resources that have come together in the collaboration, even if pushing the very top of capabilities further is risky. It is not as if people and datacenters will just be sitting around. There could be very active and exciting work on, e.g., beneficial applications, while more confidence is built on safety for the next step up in capabilities.

Conclusion

I like the vision above better than the other CERN for AI visions I’ve heard so far, and better than what I consider the default course of AI development and deployment.

But it’s not self-evidently the best course, either, or fully-specified, so I’m sharing it in the hopes that this leads to more breadth and depth of thinking on this potentially critical topic.

As a reminder, if you are interested in collaborating with me in the next phase of my career (whether my next steps are CERN for AI-related or otherwise), you can learn more about my thought process in this post and can fill out this form to express your interest.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to George Gor, Max Reddel, Katherine Lee, David “davidad” Dalrymple, Larissa Schiavo, Grace Werner, Jason Hausenloy, and Haydn Belfield for helpful feedback on earlier versions of this post. Views and mistakes are my own.

For example, the way I explained my “spicy take” on AI and inequality could probably have been clearer (though I do think it’s quite timely with the launch of ChatGPT Pro and social media discussion of whether that is worth the money/for what purposes). Also, when I referred to people working on the issue of AI sentience as “fringe nerds,” it perhaps wasn’t obvious enough that I meant that term in an endearing sort of way (the world is moved forward in part by people putting their necks out on temporarily-fringe topics until they become mainstream, and my larger point was that the issue will become more mainstream over time regardless of whether AIs are in fact sentient or not).

First, it’s bad form to explain other people’s opinions away on the basis of bias, and I should have focused squarely on the substance of the issue. In my defense/while we’re on the topic, when I say that there may be biases at play, I don’t mean that as a comment on anyone’s character. I think biases and responding to incentives are totally natural, and in fact, I left OpenAI partly to change my own biases/incentives. And of course, people don’t always act according to their financial interests.

Second, it’s not even 100% clear that a CERN for AI (as defined above) would be against the financial interests of people and organizations in the AI industry today. I discuss this later in the blog post. Granted, there are variants of “CERN for AI” that could cause a collapse of various AI company stocks. Consciously or unconsciously, this fact likely influences some people’s thinking, which is why I mentioned it and don’t think it’s a crazy point (even if it’s not where I should have started my response). Governments are indeed quite capable of setting back industries with heavy-handed regulation. But there’s a difference between being opposed to naive/bad versions of an idea and being opposed to the entire family of ideas. I expect there are versions of a CERN for AI that many individuals and institutions in industry would support.

Third, I was being inconsistent. In other parts of the discussion, I said that more people should flesh out good versions of the idea, with the implied premise being “more, better details = more support.” But when asked about the lack of interest, I forgot about this and said a bunch of other things.